Family Tapestry

Choosing our own colours

Every family has its stories. The ones you grow up hearing, half listening, the ones which imprint themselves on your subconscious, so you feel as though you somehow knew those distant aunts and great uncles in their high collars and voluminous skirts. The story of Clara and the joiner was such family tale.

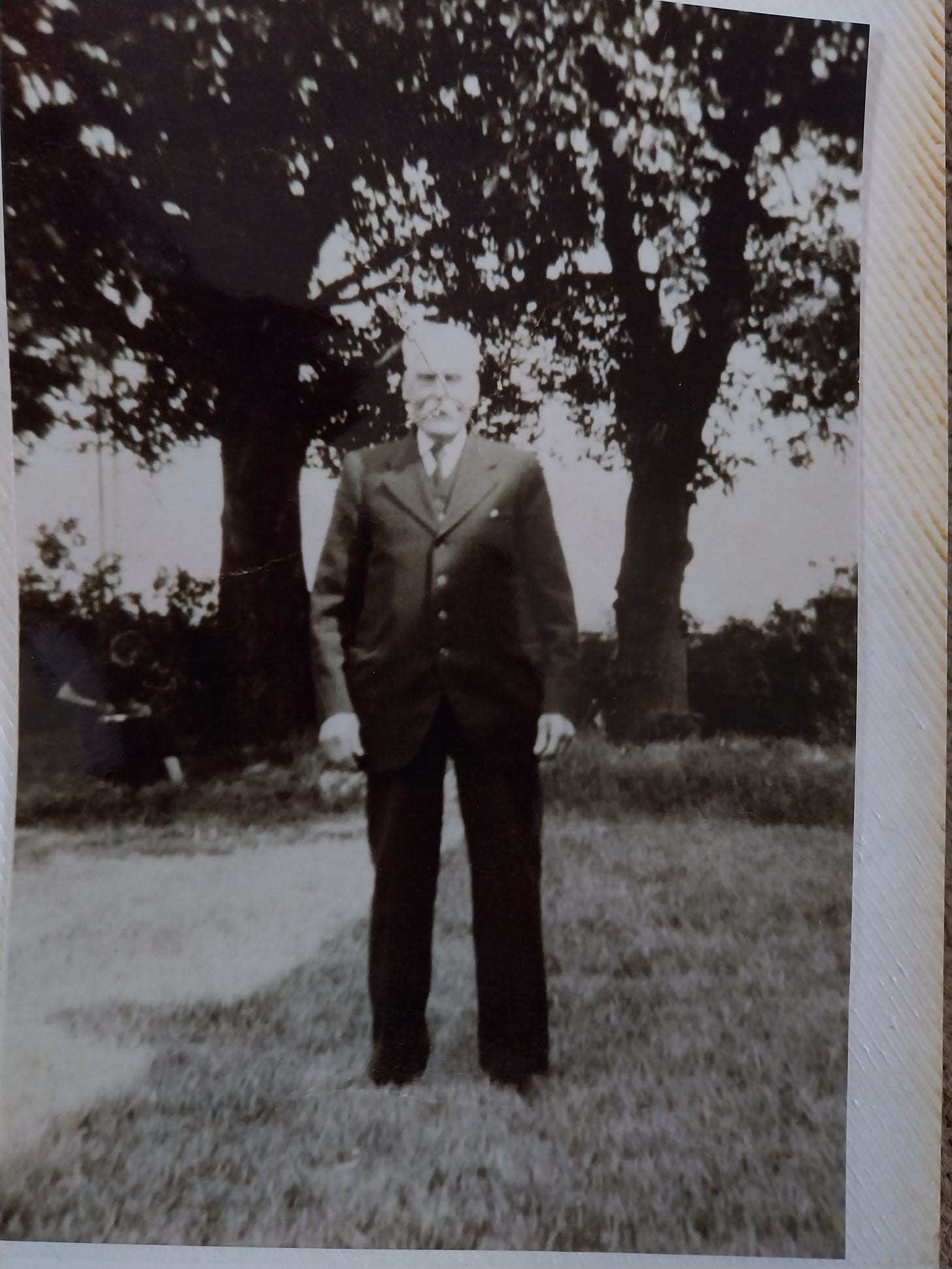

Once upon a time, around the year 1880, there was a girl named Clara and she was the daughter of a well to do man, an Auctioneer and Valuer in the Isle of Axholme. JB Taylor, his name was always spoken with reverence and only ever by his initials. Though none of the people who had met him were still alive by the time the tale was told to me. The Taylors lived at Cumberworth Lodge, a comfortable and sizeable property in Graiselound, a small village just outside the larger village of Haxey. By all accounts JB Taylor thought well of his position in life and aspired to be the owner of a grand property and he decided to have a new staircase built with a glass dome in the roof above. He employed a firm of master joiners from Doncaster. Which brought Harry Moorhouse into Clara’s life.

Their story is told, in the family, as one of pure romance. The daughter of the house and the young craftsman, falling in love across the class divide, and in the absence of parental approval, eloping to be married and, presumably, living happily ever after. The End

Over the years I picked up fragments which threw doubt on this received version. A dead first wife and stepchildren surely meant Harry wasn’t as young or innocent as satins and velvets, he story portrayed. The terraced house in Hexthorpe where they brought up their children, a far cry from the spacious rooms of Cumberworth Lodge and suggesting cramped living and tight purse strings. But I am drawn by the story which played out in the Isle of Axholme and became family legend.

I have visited the Lodge and seen the fine wooden staircase and the sun casting rainbows through the coloured glass in the small dome above. The house is a care home now but I have sat on the window seat at the top of the stairs and looked out towards the road along which Harry would have arrived and I have imagined Clara seeing him for the first time. And that is where even family folklore ends and imagination begins.

I have imagined a whole courtship for Clara and Harry. There is a wildflower meadow not far away, with a bench by a tumbling beck and I have cast it as the setting for the romance, though there is no basis in fact. I wrote a short story about the two of them meeting by the bench, sitting side by side among the wild flowers and now, in my mind, it is fact. I have seen them there in the springtime when the hawthorne was thick in the hedges and Clara’s skirts brushed though the cowslips and speedwells. Though, in fact, it was me sitting by the Beck, listening to the chatter of water over the stones. I was Clara in my imagination and now it has become part of her story.

And it got me to wondering where reality and imagination meet and whether every family story isn’t in fact woven from threads of reality and projection and longing. I see the family story as a tapestry, where a careful choice has been made, by the teller, of the colours they will weave. My great grandmother, unable to criticise her parents and seeing all they did in a romantic haze chose pinks and lilacs and soft lemons. My aunt, a younger generation and bristling with morality might have chosen greys and sombre navy, creating a sobering tale of mistakes made and consequences lived with. Whereas I choose greens and sky blue and weave the story of Clara and Harry into the landscape where they lived and breathed. I embroider forget me knots round the edges and fashion lacy clouds. A local garden of Eden for their story.

But how would they tell their own story? What colours and textures would they use? Would the crimsons and scarlets of that first headlong rush remain? Or would they fade to everyday browns and beige, comfortable, accustomed threads? A tapestry on the wall that no-one, any longer notices. Or would they weave their tale in black and blue and purple, for their bruised and battered souls after a lifetime of trying to live up to a great romance? Did they wish the story had ended a chapter earlier so it could always have been recalled in the softest tones of blush and dove and silvery sweet regret?

I will never know. I write my own version of the story and it is both as true and as false as all the other versions, even those told at the time to save face, to justify, to excuse and to celebrate. Because we are all weaving stories, all the time. Choosing our threads from the basket of colours, stitching ourselves in and out of the narratives of our lives and of our land. I guess this means I get to choose my own colours. I can pick the ones which make my heart happy, the pinks and violets and sunshine lemon. Or I can choose the ones which weigh me down, khaki and pewter and dun. I can choose a new colour every day. And sometimes other people will tell my story and they’ll choose different shades, ones I wouldn’t recognise. But that’s OK because we’re all characters in our own stories and in everyone else’s stories too. In the end it is all one story and one great tapestry and our single threads will blend perfectly into the whole.

You've invoked a possible reality that resonates with you, that makes sense to the storyteller in you as well as to the family member in you. Tiny snippets of family history tell only a part of the story, the bare facts of certificates, the wistful retold remembrances, and we each judge the teller and the telling based on our own experiences.

I imagine they would approve of your forget-me-not embroiderings around their lived experience. I think they'd appreciate the tale you are telling of them. I know I did!